Introduction

In an earlier post I described Atomic Programming which is a novel approach to building software systems. The idea is to decompose systems into quite small components called atoms, each of which is easily and quickly buildable by the LLM with a low error rate. This is based on the general observation that LLMs are dramatically more effective when we keep their cognitive load low — what I call hypercompetence. Atomic Programming tries to keep the LLM in its hypercompetent “golden zone” all the time, so while I still need to make product and architectural decisions, the time spent on implementation becomes vanishingly small.

The purpose of this post is to walk through actually creating a system using the Atomic Programming approach. This is a “real” system meaning it addresses a need I am actually experiencing in real life, and I feel that if I can build the system I have in mind it will address that need sufficiently well that I would use it regularly — on a daily basis.

Superpage

The system is called Superpage. Its purpose is to make me a more efficient consumer of Hacker News content. I visit the HN homepage most days and get a huge amount of value from it — both the articles and the discussions. But I know there’s more value to be had if I spent more time on the site. At the same time, I don’t want to spend more time on the site — or more accurately, I don’t want to spend less time doing other things. The vision for Superpage is to be a kind of “time multiplier”: half an hour spent on Superpage will be like spending several hours on Hacker News itself.

The MVP addresses the stories I flat out miss. In between my daily visits, stories resonate with the community, accumulate points, rise to the front page, spark interesting discussions, and then descend and disappear — all before I check in again. More than once I’ve Googled something and found a Hacker News thread with hundreds of comments from just days ago — it had come and gone between my daily visits.

Superpage addresses this by widening the aperture. It monitors the front page frequently so I don’t have to, stores what it finds, and gives me tools to sort, filter, and search through everything that’s come and gone since my last visit.

The Build

Going in, I treated Atomic Programming as an interesting but naive vision. Now I would see what happens when that vision meets reality. Reality is always more complex than what we imagine. This journey would show me which parts of Atomic Programming are strong and which need to evolve. And that’s exactly what happened — which is not to say the journey is finished. It’s more like going from looking at a map and imagining the trip, to actually journeying that first leg.

I started with a small “Starting Point” — a simplified version of the MVP that was easy to build but gave me something real to work with. From there I iterated four times, with the system usable at the end of each iteration. Below I describe each step in some detail, with expandable sections for those who want to dig deeper. After each step, I share what I learned and how it informed what came next. At the end there are some overall reflections, and a link to all the prompts and source code.

Starting Point

I started with something simpler than the full MVP — easy to build, but a reasonable foundation to iterate from.

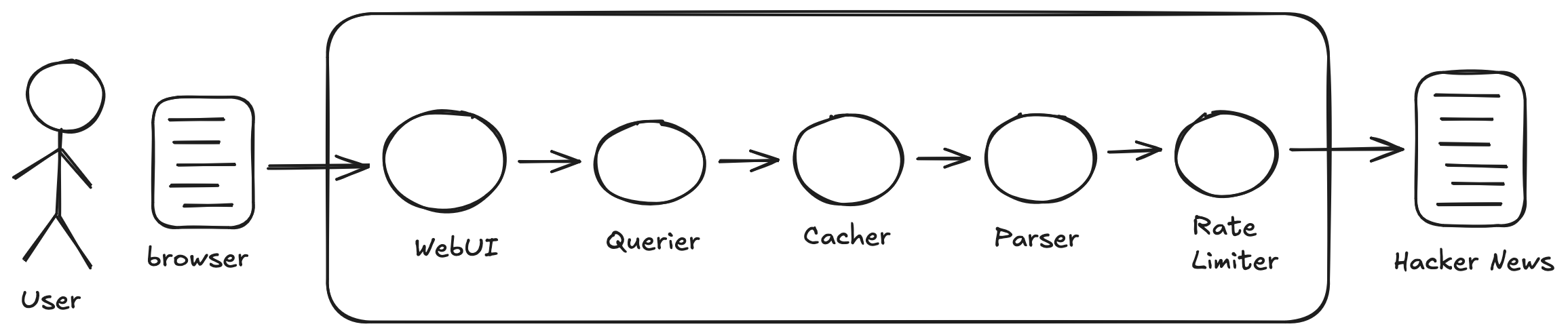

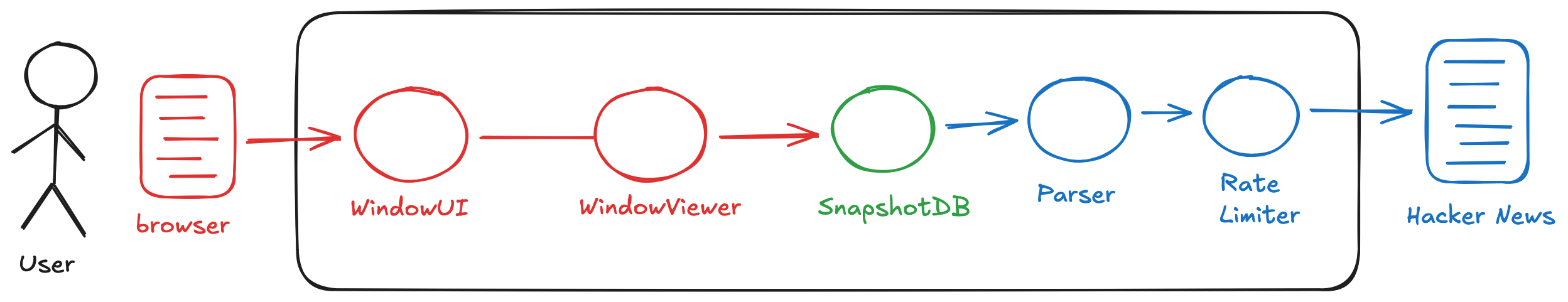

Rate Limiter fetches HTML from Hacker News while enforcing a minimum interval between requests — keeping us a good citizen of the internet. Parser pulls pages from Rate Limiter, extracts the story data (headline, URL, points, comments, rank, age, etc.), and returns structured JSON. Cacher stores the parsed data in memory with a TTL, so we’re not hitting Hacker News on every request. Querier applies filters and sorts to the cached stories — filter by points, by age, by number of comments. WebUI serves a web page that talks to the Querier — the only atom without a REST API, just HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, with a Go server proxying requests to the backend.

This came together in a couple of hours — and most of that was me thinking through different approaches and landing on an architecture, not waiting for the LLM to code. I expected flaws — and that was fine. Having actual running code is always a great reality check; I was getting firsthand experiential knowledge rapidly, and I knew I could rebuild parts or all of it just as fast. Two things stood out.

The Cacher was silly in retrospect. I was trying to avoid database complexity while still storing content locally — a reasonable instinct, but the TTL approach was flawed in a way I realized even before using it. As the atoms came together, I could see what would happen: the cache refresh had no relationship to what the user was doing. Change a filter, and depending on timing, the system might pull fresh content from Hacker News. The UI would go slow, and worse, show you different stories than what you’d been looking at. You’d ask to filter the content you were seeing, but the filter would apply to new content that arrived because of the TTL. That became the first thing to fix.

The UI was clunky too, but that was fine. I’d pointed Claude at the Querier’s API and said “build an appropriate UI for that” — maybe ten minutes of effort. What I got was functional but unoptimized: too many clicks, wasted vertical space, unnecessary labels. It served as a placeholder, though, which was exactly what I needed. It let me interact with the system and exercise its features while I focused on evolving the backend. The real UI work would come later.

The Prompts — full prompts of the Rate Limiter and Parser with commentary.

Here are the full prompts for Rate Limiter and Parser. The other atoms follow the same structure.

Rate Limiter:

This is a new greenfield project. We will build this in Go. It is called Rate Limiter. The executable will be called “ratelimiter”.

The purpose of the Rate Limiter is to fetch HTML docs from URLs, but to rate limit itself so as to not be a burden upon the remote website.

The Rate Limiter will have two required command line arguments. —rate <num-sec> specifies a number of seconds as a positive integer. The semantics are that the Rate Limiter will make at most one HTTP request every <num-sec> seconds. —api <port-no> specifies the port number where the Rate Limiter’s REST API can be accessed.

The REST API will have an endpoint POST /fetch which causes the Rate Limiter to fetch a URL. The URL to be fetched is specified in the request body. The response body contains the HTML document retrieved from that URL. The request and response bodies are both JSON objects. If a request arrives too soon vis-a-vis the rate limit, then the request will block until the Rate Limiter is able to provide a response.

The REST API has another endpoint GET /doc which returns detailed documentation of the entire REST API, including example requests and responses. The documentation does not need to concern itself with system internals or how to operate the system – it is only for clients of the REST API.

When you are done coding make sure the system builds and runs correctly, then write a detailed README in case another developer needs to debug or enhance this system in the future.

Parser:

This is a new greenfield project. We will build this in Go. It is called Parser. The executable will be called “parser”.

The Parser is part of a larger system. It depends upon a component called the Rate Limiter. Use curl to GET /doc from localhost:8080. That is the documentation for the API of the Rate Limiter.

The role of the Parser is to obtain the current top stories from Hacker News and parse them into structured data. It will do this in response to client requests to its REST API. The Parser will not interact with Hacker News directly, rather it will use the Rate Limiter to obtain the HTML documents for Hacker News URLs: https://news.ycombinator.com/, https://news.ycombinator.com/?p=2, https://news.ycombinator.com/?p=3, and so forth. The number of pages it pulls from Hacker News is determined by a required command line parameter. It will then parse the content from those pages and return that information to the client as a single JSON object.

The Parser will have three required command line arguments. —api <port-no> determines which port number the Parser listens for HTTP requests to its REST API. —ratelimiter tells the Parser which localhost port the Rate Limiter is listening on. —num-pages <N> tells the Parser how many Hacker News Pages to pull (must be a positive integer).

The REST API will have an endpoint POST /fetch through which clients will obtain the Hacker News content. When a request arrives from the client, the Parser will request the N URLs from the Rate Limiter sequentially – no need for concurrency. When the Rate Limiter has the HTML documents it will parse them and construct the JSON object to return to the client. The object will have some top-level metadata about the N documents (when they were fetched, and so forth), as well as an array of stories. For each story there is a JSON object with fields for the headline, the URL of the article, the username of the submitter, the number of points, the number of comments, the URL of the discussion page, the story id (HN’s identifier – so that we can track stories over time if we like), the story’s current rank, and the story’s page as two fields: the units (hours, days, etc.) and the age measured in those units (this mirrors the information HN displays in its web pages).

The REST API has another endpoint GET /doc which returns detailed documentation of the entire REST API, including example requests and responses. The documentation does not need to concern itself with system internals or how to operate the system – it is only for clients of the REST API.

When you are done coding make sure the system builds and runs correctly, then write a detailed README in case another developer needs to debug or enhance this system in the future. To test the system you will use curl to obtain the structured data from the Parser and then also use curl to pull the actual HTML from Hacker News and make sure the two align.

What these prompts share: The first few lines are boilerplate — greenfield, Go, name, executable. Then a sentence about the atom’s role in the larger system, providing minimal but useful context. Then command line arguments for configuration — port numbers and functional parameters. Then the REST API, which is the core of the atom’s definition. Finally, GET /doc and instructions to test.

What they leave open: Notice what the prompts don’t specify: JSON field names, internal structure, error handling details. I describe the capability needed, not how to implement it. The LLM makes reasonable choices, and reasonable is good enough. This is high leverage — short prompts are fast to write and fast to modify. I’m sketching intent and letting the LLM fill in the rest. The less the definition spills into implementation details, the more freedom I have to iterate.

I do specify POST /fetch explicitly, but only because otherwise Claude tends to ask what the endpoint should be called. That question is a waste of time.

The /doc endpoint: Every atom exposes GET /doc, returning documentation of its API. This is how atoms discover each other during development. The Parser prompt tells Claude to curl the Rate Limiter’s /doc endpoint to understand what it’s working with. Claude can also call the API directly — blurring the line between understanding the system and testing it.

Why coupling is fine: Traditional API design tries to decouple components — hedge against future changes you’re only guessing at. With Atomic Programming, the calculus shifts. We can respond to changes when we know what they are, rather than guessing upfront. If three atoms are tightly coupled, throw them all away and rebuild all three. That’s not scary when each takes minutes. Coupling makes larger changes more likely, but it also makes those changes cheaper.

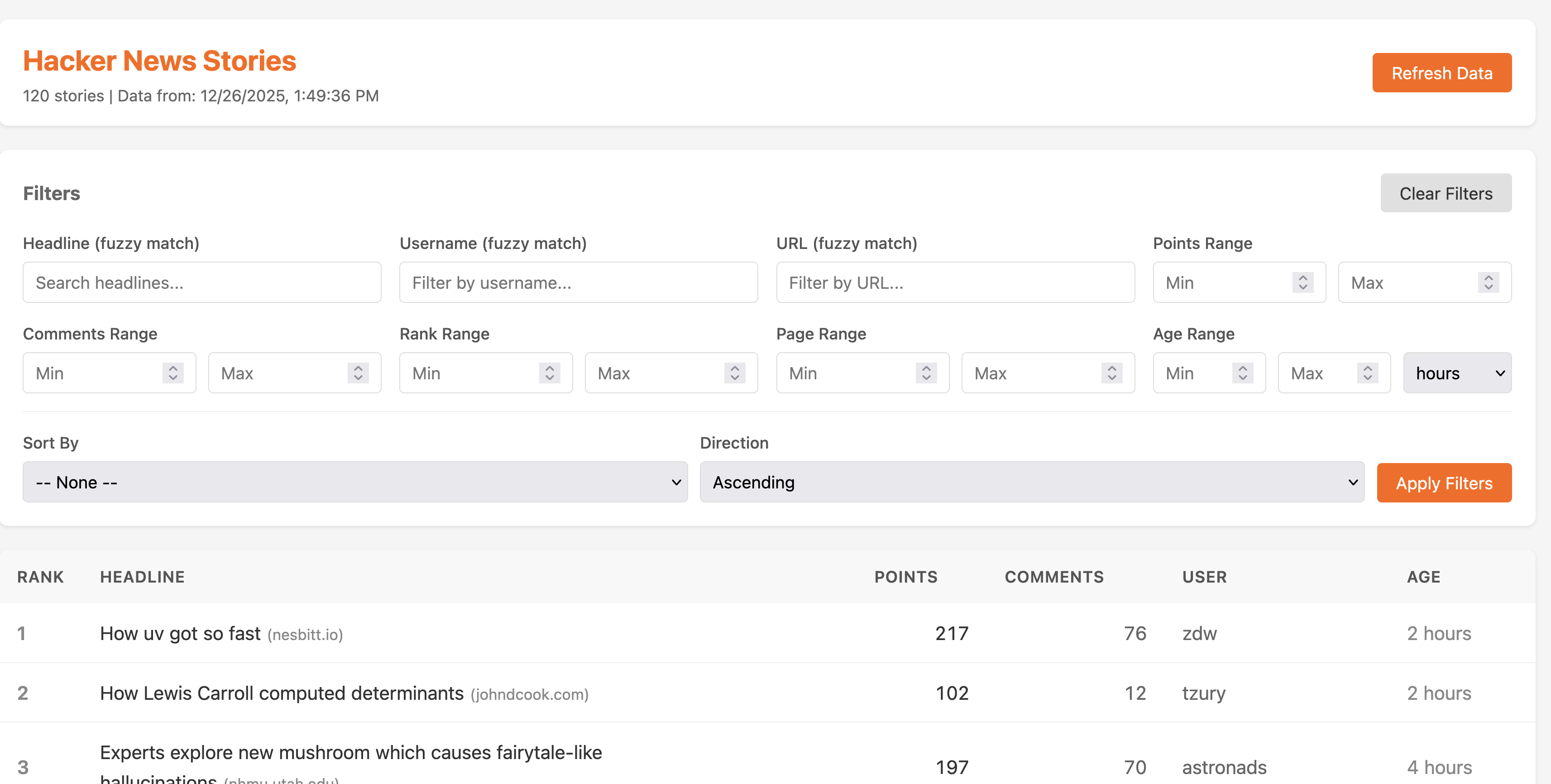

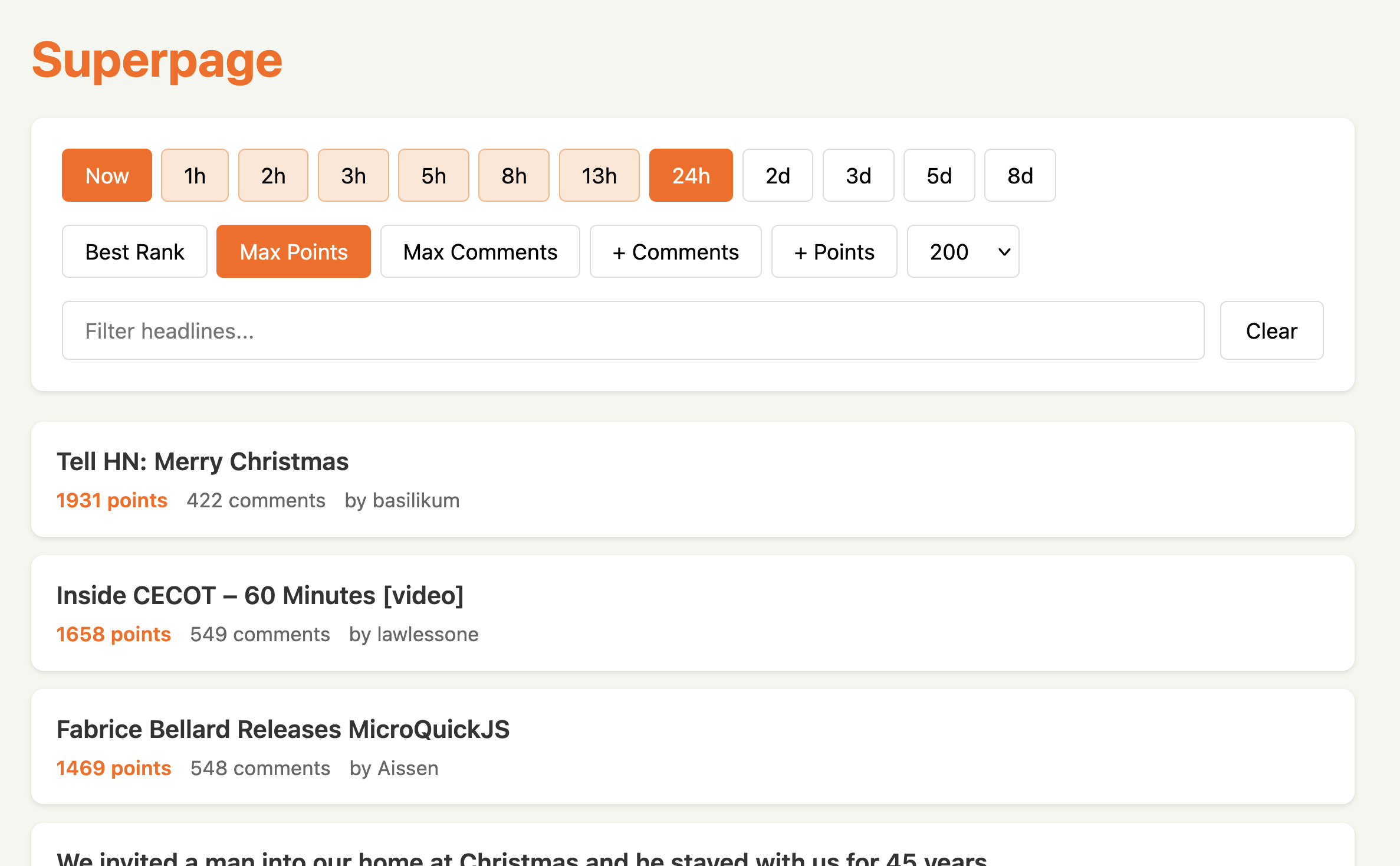

User Interface — screenshot of the initial UI.

The placeholder UI that Claude generated with minimal guidance. You can see the inefficiencies: every filter control takes up its own row, wasting vertical space that should go to the content. The labels are redundant — “Min Points” next to an input field labeled “Min Points.” Every change requires multiple clicks. The sorting controls duplicate the filter layout pattern even though they work differently.

(Note: the “Refresh” button visible here is actually from the next iteration — that’s the screenshot I had on hand. In the true Starting Point, the refresh was automatic via the Cacher’s TTL, which as discussed was a flawed design.)

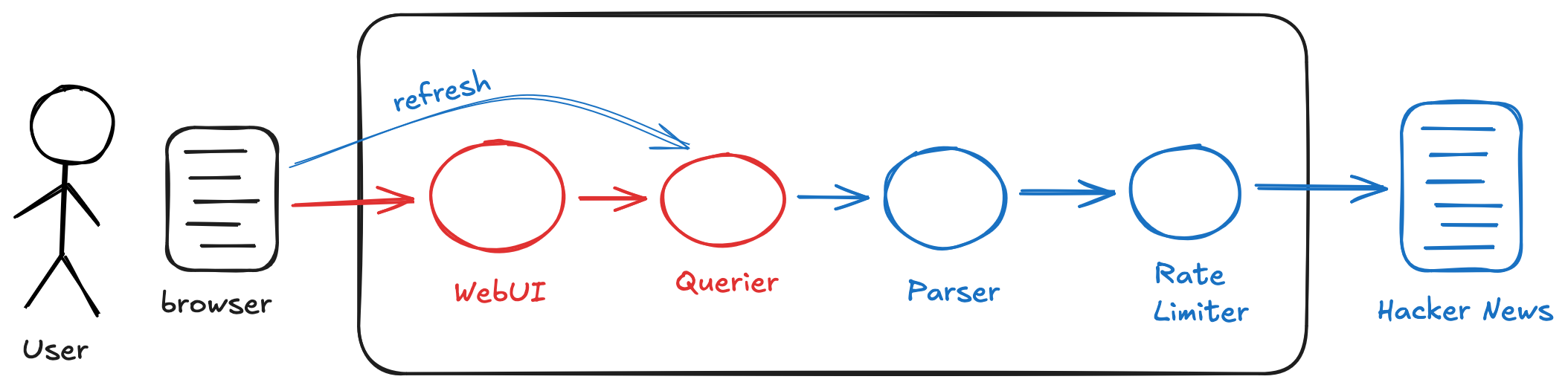

Iteration 1: Adding Refresh

To address the cache TTL issue, I removed the Cacher entirely and added a notion of “refresh” to the system. Now the Querier holds content in memory and exposes an endpoint to trigger a refresh — discarding its data and pulling fresh content through the Parser, which in turn hits the Rate Limiter and ultimately Hacker News. The WebUI gained a refresh button to invoke this flow. I threw away the Cacher and its prompt, rewrote the prompts for the Querier and WebUI, and rebuilt both — about two hours including thinking time.

In some ways this felt odd — I was immediately making significant architectural changes to a system I had just built, knowing that even after these changes I still wouldn’t have an MVP. Several more iterations would be needed for that. But the cost of iteration was low, and there was something clarifying about working with an actual running system I could use and observe. “Build one to throw away” was becoming “build many to throw away” — each version getting me closer, none needing to justify itself beyond what I learned from it.

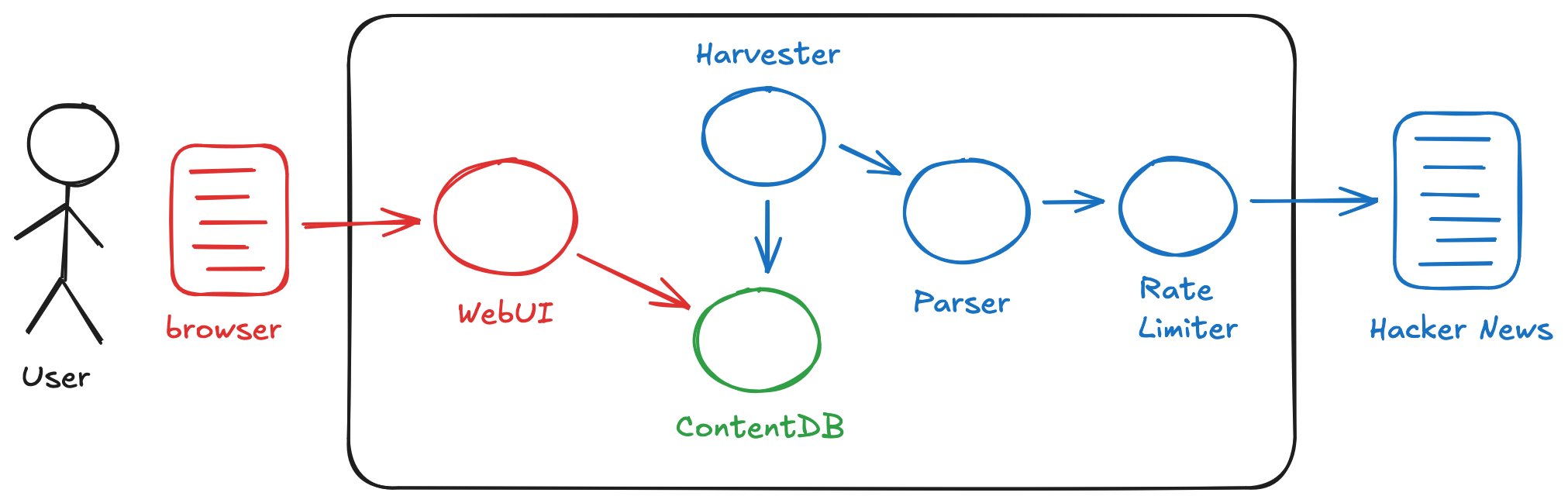

Iteration 2: Moving to a Database

The refresh concept from Iteration 1 made the system more usable, but I wanted to evolve it further — moving from user-triggered refreshes to automatic harvesting of Hacker News content at a set frequency. The idea was that this would happen continuously, regardless of whether I was using the application, which furthered the overall vision of decoupling my consumption of the content from the interactions with Hacker News itself. Since this meant storing significantly more data, I also decided to move from in-memory storage to on-disk persistence.

I replaced the Querier with ContentDB — a SQLite-backed store — and added a Harvester to periodically pull content from the Parser and write it to the database. The ContentDB API had two main endpoints. The write endpoint allowed the Harvester to store content obtained from the Parser as-is — the same JSON object, no transformation. The read endpoint was similar to the earlier Querier API but with the addition of start and end times; ContentDB would aggregate the data within that time span and then apply filters and sorts. The WebUI was rebuilt to include specification of the time span.

Collaborating with Claude on the API design was something of an epiphany. Because the Parser was already up and running, Claude could inspect its API and propose a straightforward approach: have the ContentDB write endpoint accept the Parser’s output as-is, same JSON structure, no transformation. The same pattern repeated when building the WebUI — Claude designed it against the running ContentDB API. This was shifting my sense of Atomic Programming. I had been thinking of atoms as standalone, well-understood components. But what was emerging was more incremental: each atom defined with respect to those that preceded it. The tradeoff is less modularity, but you gain speed. I was already working at something like the speed of thought, and this approach reduced that “thought” further by removing the cognitive load of designing clean abstractions upfront.

When I engaged with the full system as a user, I ran into quality issues. Queries that should have returned stories came back empty; filters that worked in isolation failed when combined. I tried debugging with Claude, but it didn’t go well — more than once Claude declared victory while bugs persisted. I was out of the golden zone. My diagnosis: ContentDB was doing too much.

Iteration 3: Splitting ContentDB

My response was to simplify. I doubled down on the KISS snapshot concept that was already present in the Parser and the ContentDB write endpoint. SnapshotDB would not only store content as snapshots — that’s also how content would be read. You provide start and end times, and you get back an array of snapshots. With this design, the Harvester was doing almost nothing — an odd pass-through atom. So I added scheduling functionality to SnapshotDB itself; it pulls directly from the Parser on a set interval. One less atom to manage.

For the query logic, I created a new atom: Window Viewer. Its API was equivalent to ContentDB’s read endpoint — a time span plus filters and sorts — but the implementation was simpler. It pulls the relevant snapshots from SnapshotDB and applies the “window” logic to compute the result. I rebuilt the UI (renamed Window UI at this point) and pointed Claude at the Window Viewer’s API.

This time the system was stable when I actually used it. The approach felt validated — both Atomic Programming in general, and the more incremental, less modular style that had emerged along the way.

Iteration 4: Window UI

With the backend stable, I returned to Window UI. As noted earlier, Claude had produced something functional but clunky with minimal guidance — too many clicks, wasted vertical space, redundant labels. I’d left it as a placeholder while figuring out the rest of the system. Now it was time to optimize.

I’m happy with where this came out, but surprised by how I got there. This was another example of Atomic Programming evolving organically in real time. Making the UI good meant lots of small tweaks and trying different ideas, and I naturally did this in direct collaboration with Claude Code: we discussed a change, Claude implemented it, I tried it. Having a modified UI running live on top of a real system in seconds was remarkable. We collaborated for maybe an hour and came up with what I feel is quite a good design. But I was never able to find my way back to a prompt — which tells me the Atomic Programming idea of prompts as source of truth needs to be more nuanced. I think this is specific to UI, where I’m sensitive to small details in a way I’m not with other atoms.

The optimizations covered layout and interaction: consolidating controls into fewer rows, removing redundant labels, reclaiming space for content. The most sophisticated change was the time range selector.

How to manage UI atoms without a prompt as anchor is something I’m still working out. My intuition is that source code will end up being the source of truth — detailed specifications and diagrams seem like unnecessary overhead. But I’m not confident the LLM can revise the same codebase indefinitely; my expectation is that it will eventually become bloated and internally disorganized. I don’t yet know how to address that. The other thing I suspect is that UI tinkering will be an ongoing process — I don’t think the UI layer will ever be “done” and frozen. This touches on a whole aspect of Atomic Programming I have yet to explore: how it impacts conventional notions of deployment and change management. That’s an exercise for the future, but I think it will also shape how UI atoms are ultimately managed and represented.

Time Range Selector — details of how the two-step range selector works.

I wanted Fibonacci-scaled intervals (1h, 2h, 3h, 5h, 8h…) as a single row of buttons, with two always selected to mark start and end of the range. This created a UX puzzle: when you click a new button, is it the new start or the new end?

The solution was a stateful two-click interaction. Initially two buttons are selected showing the current range. Click any button and it highlights differently — pulsing to signal the system is waiting for a second click. Click another button and those two become the new range. If you don’t click within a few seconds, the animation stops and it resets.

This emerged through iteration. The first implementation had the puzzle but no solution — clicking a button produced unpredictable behavior. Claude and I tried several approaches before landing on the stateful model. The animation was Claude’s suggestion.

Overall Reflections

Going through this process, I was struck by how much of what I’m used to doing as an engineer reflects a world where implementing ideas is expensive. Detailed specifications, careful upfront analysis, clean abstractions to decouple components — these are all insurance against building the wrong thing. You invest in planning because mistakes are costly to fix.

But the economics are shifting. Building the wrong thing isn’t expensive anymore — not when you can throw it away and rebuild in a couple of hours. And you learn so much faster from actual running code than from artifacts that try to model it through abstract concepts. A specification is a guess about what the code should do; running code is the thing itself.

What fascinated me most was realizing how internalized those old economics are. Even knowing that rebuilding was cheap, I still felt the pull toward upfront design, toward getting it right the first time. That instinct doesn’t disappear overnight. But this journey made it visible — and that feels like the first step toward something new.

Appendix: Prompts and Source Code

The prompts and source code are on GitHub. Looking back, each iteration should have been a commit — but I only thought to share this after the journey was underway. The repo reflects the final state.